You are here

Book of Mormon Central is in the process of migrating to our new Scripture Central website.

We ask for your patience during this transition. Over the coming weeks, all pages of bookofmormoncentral.org will be redirected to their corresponding page on scripturecentral.org, resulting in minimal disruption.

Easter Reflections Day 1: A Week of Completions

The last week of Jesus’s mortal life was a time filled with completions. As His time drew near, He knew that many parts of His mission needed to be drawn fully to conclusion. And by the time that week ended, He had in fact finished all that He had been sent to do and all that was necessary to allow the eternal plan of His Father to succeed.

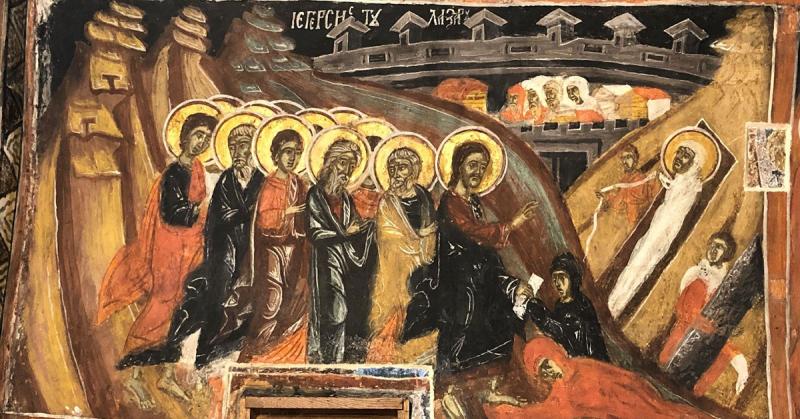

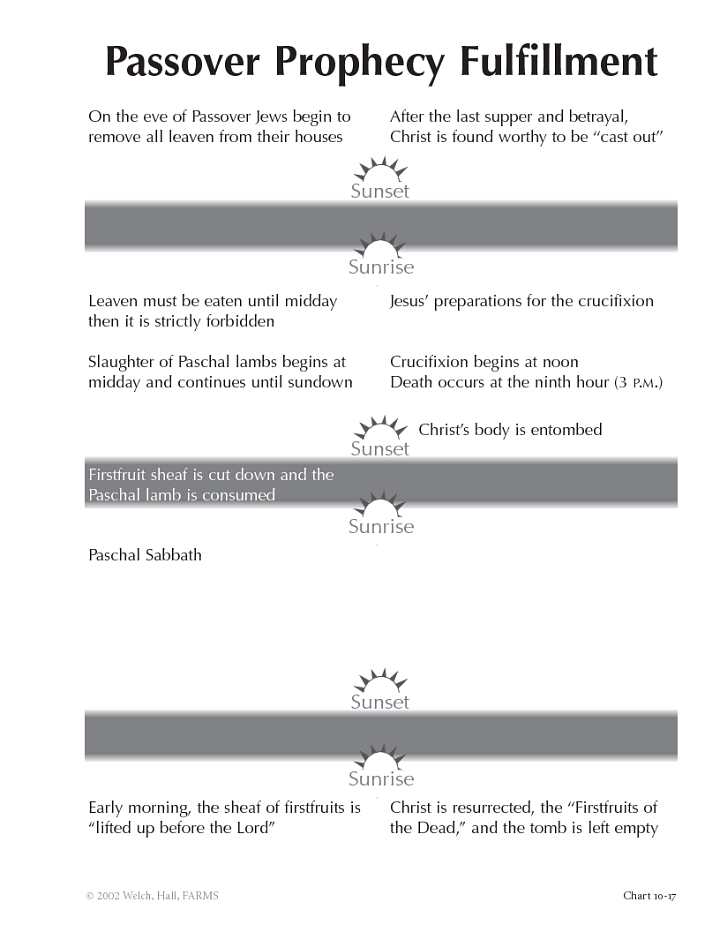

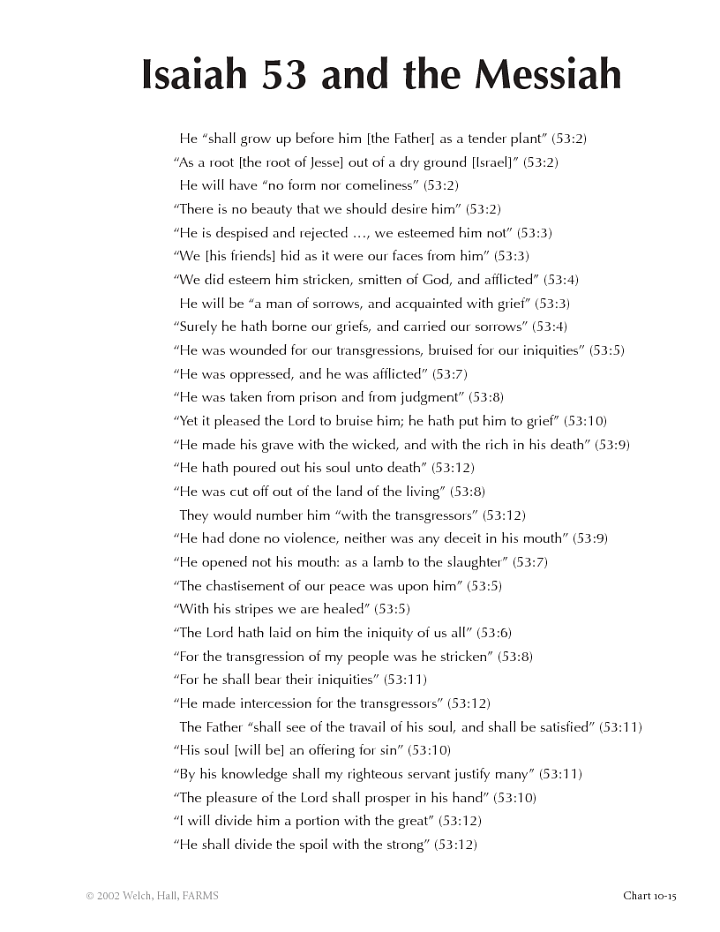

Prophecies needed to be fulfilled. The week began with his Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem, fulfilling a host of prophecies, beginning with the coming of the king riding on the foal or donkey (Matthew 21:5–7; in fulfillment of Isaiah 62:11 and Zechariah 9:9). As the week progressed, Jesus embodied the similitudes that were long before embedded in the celebration of Passover (see Figure 1). The hours on Calvary saw the actualization of prophetic anticipations in Psalm 22, a psalm of King David, who had long before foreseen this Son of David (Acts 2:30–31). The week ended poignantly as the striking prophecies in Isaiah 53 of this Suffering Servant came to pass (see Figure 2), as our Savior went “as a lamb to the slaughter,” so that “with his stripes we are healed” (Isa. 53:5, 7).

Figure 1 Passover Prophecy Fulfillment

Figure 1 John W. Welch and John F. Hall, "Passover Prophecy Fulfillment," in Charting the New Testament (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2002), 10-17.

Figure 2 Isaiah 53 and the Messiah

Figure 2 John W. Welch and John F. Hall, "Isaiah 53 and the Messiah," in Charting the New Testament (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2002), 10-15.

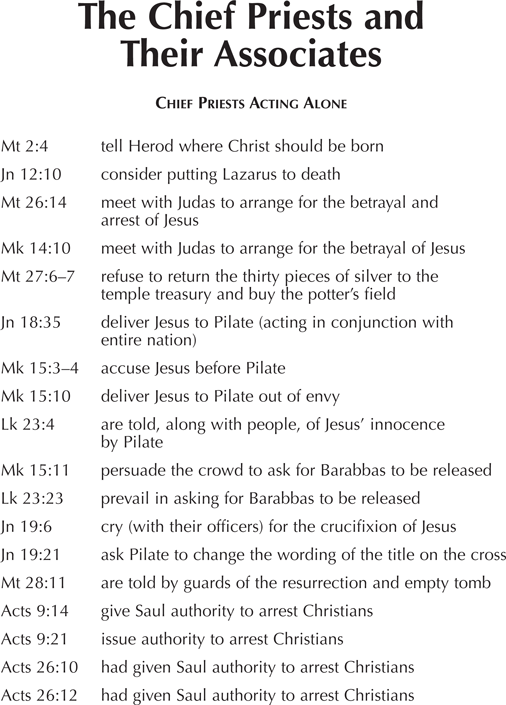

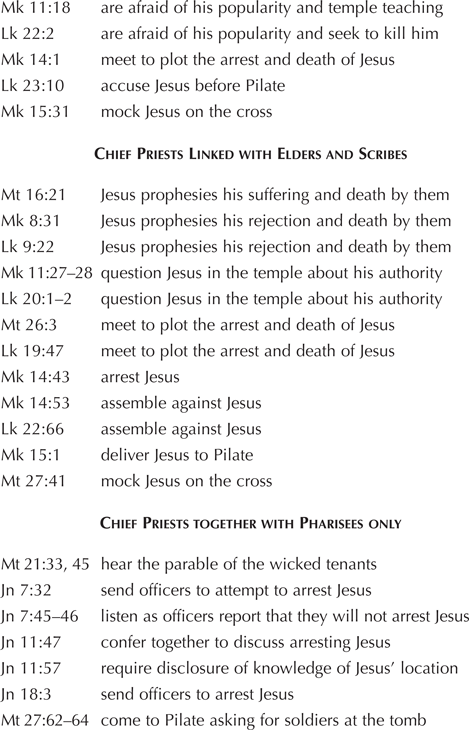

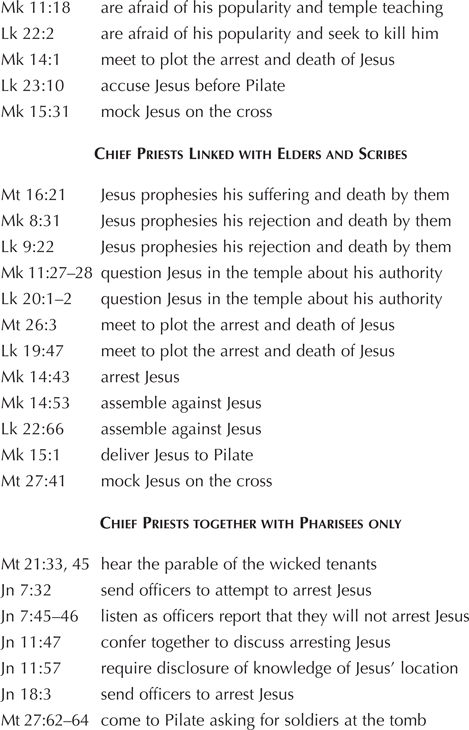

Certain people also needed some final attention. As the Gospel of John tells us, Jesus loved Lazarus and his sisters Mary and Martha, and He stayed again one last time in their home in Bethany, returning for three or four nights during this week. In previous visits to Jerusalem, Jesus had made friends with important people in Jerusalem, such as Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea. While He had left some Pharisees unsettled during his previous visits, no doubt He would have wanted to finish some of those conversations and reconcile with them if at all possible. Perhaps he succeeded, since the Pharisees seem to have taken a less prominent role during this final week, when it was Caiaphas and his Chief Priests, linked with their Scribes and the Elders, who aggressively took the lead (see Figure 3). Meanwhile, the multitudes held Jesus to be a prophet (Matt. 21:46).

Figure 3 The Chief Priests and Their Associates

John W. Welch and John F. Hall, "The Chief Priests and Their Associates," in Charting the New Testament (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2002), 3-9.

People who had rejected Jesus needed a final chance to change their minds and ways, and Jesus fulfilled that need. He personally confronted people who vigorously opposed Him, even to the point that they perceived that he spoke in the parable of the Wicked Tenants against them (Mark 12:12; Luke 20:19). He lamented the impending destruction of Jerusalem, giving the whole city one final prophetic cry, urging them to repent and to come unto His protection, as a hen gathers her chicks (Matt. 24; Mark 13; Luke 21). Herod Antipas, the tetrarch of Galilee who had killed John the Baptist, was given one last chance to rethink what he had done (Luke 23:6–12). The epitome of forgiveness, Jesus even forgave those who knew not what they were doing (Luke 23:34).

Jesus’s teaching of the people of Israel also needed to be completed. Teaching them daily in the temple for three days, Jesus completed his climactic series of parables in Matthew 25. There he told the people to be like the five wise bridesmaids in preparing for the Coming of the Lord. He inspired them to be faithful stewards in magnifying the talents with which they had been entrusted by the Lord. He admonished them to be counted among the Lord’s sheep, and not the goats, in anticipation of the final day of God’s judgment and separation. And He assured them that the righteous who have ministered “unto one of the least of these my brethren” shall enter “into eternal life” (Matthew 25:40, 46).

Jesus also needed to give His apostles one final private session of intense training and love. The week’s instruction culminated at the Last Supper. There Jesus and his disciples partook of the covenantal bread and wine of remembrance. Then Jesus delivered a finale of immortal statements: “a new commandment I give unto you, that ye love one another as I have loved you” (John 13:34), “in my Father’s house are many mansions” (14:2), “if ye love me, keep my commandments” (14:15), “my peace I give unto you” (14:27), “I am the True Vine and ye are the branches” (15:5), “for the Father himself loveth you, because you have loved me” (16:27), “this is life eternal, that they might know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou has sent” (17:3), “for their sakes I sanctify myself, that they also might be sanctified through the truth” (17:19), and “that they all may be one; as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be one in us” (17:21). The five incomparable chapters of John 13–17 make a sublime set of readings at the heart of the Easter Week. It is as if Jesus had saved His best doctrinal wine for last.

And, on top of all that, the greatest of His daunting challenges and miraculous victories still remained to be completed that week. His Atonement, His conquest of death, and His Resurrection would be the exquisite conclusion of this week, and he could finally say, “It is finished” (John 19:30).

But as Jesus came to Jerusalem at the beginning of this week, one other final score also remained to be settled. About a month before this final week, Jesus had crossed paths with Caiaphas, the High Priest, the most powerful man in the land of Judaea. The undercurrent of that conflict runs beneath everything else in this climactic week. As the pressures build, that current churns and eventually boils over, in spite of all that Jesus could do or say. That outcome all began with the raising of Lazarus. Symbolically foreshadowing the resurrection of Jesus Himself, the raising of Lazarus from the dead was more than the proverbial last straw. It was the showdown of Caiaphas, the high priest appointed by Roman authorities, and another High Priest, the Son of the very Eternal God (Psalms 110:1, 4; Hebrews 9:11; 10:21).

Flashing back, the week of the first Easter had begun with Jesus’s Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. On that day, as huge crowds had begun arriving in the Holy City for the coming Passover, many people made a special effort to welcome Jesus. They carried branches of palm trees (John 12:13) and hoped to catch a glance of Jesus. We might wonder, Why? Why had they come? As the gospel of John says, they came precisely because they heard that Jesus, who had raised Lazarus from the dead, was coming (12:17–18). No doubt, they wanted to know if this sensational event had really happened. Some of them probably also hoped to see what Lazarus looked like, after having been raised from the dead. They shouted Hosanna, “Save Now.” They were anxious for a complete messianic victory.

Figure 4 This third-century glass plate in the Vatican Museum shows Jesus miraculously raising Lazarus and bringing him forth out of the tomb. It shows the strong faith of early Christians in this final and most powerful sign of Jesus’s power over death. Photograph by John W. Welch.

At the same time, however, there were other people in Jerusalem who were also hoping to see Jesus, but for a completely different reason. Because of the raising of Lazarus, the Sanhedrin had met a few weeks earlier and had found Jesus worthy of death (John 11:50, 53). When they hadn’t been able to locate Jesus, they had issued a public order calling for any information about his whereabouts (11:57). And then, because Jesus had fled to a village called Ephraim and could not be found, the Sanhedrin issued another order, this time for the arrest of Lazarus (12:10). Apparently they hoped that Lazarus might know where Jesus had gone. Perhaps they also wondered if Lazarus had conspired with Jesus to deceive the people. And, indeed, because of the raising of Lazarus, many people “believed on Jesus” (12:11). Having watched Jesus for quite some time (Mark 3:22–26; John 7:12, 47; 9:16, 29), Caiaphas could not allow this rising crisis to gather any further momentum.

Thus, underlying all of the many events of the final week of Jesus’s mortal life was the unfinished legal business that was set in motion a month earlier with the raising of Lazarus in Bethany, just over the hill to the east of Jerusalem. Because that remarkable event is reported only in the gospel of John, most studies of the trial and death of Jesus begin with his arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane, but that omission is short-sighted.

The raising of Lazarus had been big news, and word about it must have spread rapidly. Martha, Mary, and Lazarus were fairly wealthy. They were socially well connected. They even had their own private tomb for family burials. Many of the leading Jews had gone out to their home to mourn the death of Lazarus, but instead of mourning, they saw “the things which Jesus did” and some “believed on him” (11:45). Others were dubious, and they went immediately and reported to Caiaphas what Jesus had done. Soon the full Sanhedrin had met to deliberate how to respond.

The report given in John 11:47–57 of this meeting makes it clear that important legal steps were taken and set in motion at that time. Over a dozen words in that report have legal significance. This was not just a theological discussion, but an official legal proceeding. What was their concern? More than just recognizing the fact that Jesus had obviously worked miracles (11:47), they saw his miracles as signs, pointing to something and not just doing good. If those signs or wonders led people to “go after other gods,” then such miracles were deemed to be evil, and the law clearly required that the wonderworker be “put to death” (Deuteronomy 13:2, 5).

As the Sanhedrin then discussed the case, some argued, “If we let him thus alone, everyone will believe on him.” Others feared that “the Romans shall come and take away both our place and nation” (11:48). Here “the place” would refer to the temple, and it was especially their duty, under Deuteronomy 12, to protect the temple as the holy place.

Caiaphas, the High Priest, however, had rejected this quibbling over rationales. Saying “Ye know nothing at all,” he reasoned that it would be better that one man die “on behalf of” the people than for the whole nation to be destroyed (11:50). John says that Caiaphas did not speak these words on his own personal authority. He acted officially as the High Priest (11:51), as he authoritatively (even if unwittingly) prophesied that Jesus would die for “the people,” and not just for the people of Israel, but also so that the scattered children of God could be gathered into one (11:52). These decisive words have a ring of legal finality to them. And the Gospel of John says, “Then from that day forth they took counsel for to put him to death” (11:53). An official legal order was issued that anyone knowing of the whereabouts of Jesus needed to report that information so that he could be captured (11:57). This was not so that he could be convicted (he had already been found worthy of death), but to determine how he should be put to death, and by whom, whether the Roman procurator or the leaders of the Sanhedrin. The law might also have wanted to give any convict a chance to confess and perhaps to negotiate some settlement. But it was this basic verdict that stands as unfinished behind all that then happens the week beginning with Palm Sunday.

All Jerusalem would have been abuzz about the phenomenal raising of Lazarus, hoping and wondering if Jesus would dare make an appearance in Jerusalem for the celebration of Passover. To stem this tide, the chief priests were prepared to move quickly to apprehend Jesus (with Roman awareness, if not Roman escort), then to sentence Jesus, and get Pilate’s consent to publically execute him, all within one final early morning’s time.

Thus, as Jesus had walked toward Bethany a month or so earlier to answer the plea of his dear friends to come and heal their dying brother Lazarus, having been previously confronted by legal challenges against his miracle working, Jesus could well have anticipated that, by openly raising Lazarus from the dead so close to Jerusalem, He was effectively setting in motion the final steps leading to His own death. Knowing the risks, both on that previous occasion and equally on Palm Sunday, Jesus generously, lovingly, and willing went forward, having reassured Martha and also the whole world, with the absolutely conclusive knowledge that “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live” (John 11:25).

To be continued . . .

*Note on Header Image: This is one of many scenes that are painted onto the walls and ceilings of a seventeenth-century church in Arbanassi, Bulgaria. Here, viewers see Jesus in the center raising his right hand in blessing, as Lazarus will come forth from the stone-tomb, his burial shroud beginning to unwind. Lazarus has a gold halo, indicating his holy discipleship. He will become known as St. Lazarus. Jesus’s left hand appears to be receiving the message that Lazarus had died. The women in black and red are likely Martha and Mary. Behind Jesus are eleven disciples. Presumably Judas is the one not shown. In the lower right, a servant moves away the stone that had covered the entrance to the tomb. In the top-center, the walls around Jerusalem enclose the Temple, with the flaming altar of sacrifice on the left. Caiaphas and three other chief priests or Pharisees are in the middle, with two structures on the right. Being told by eyewitnesses about Jesus’s raising of Lazarus in Bethany, Caiaphas will convene the Sanhedrin. They will debate what to do in the face of this miraculous sign that threatens to lead everyone in Jerusalem to follow Jesus. Even miracle workers can be convicted of leading people into apostasy under Deuteronomy 13. And Caiaphas will rule that it is better for Jesus to be executed than for a riot to break out, for the holy city and temple to be taken away by the Romans, and all the people to be destroyed. An order for the capture of Jesus was sent out. Not finding Him, the Sanhedrin will further rule that Lazarus also was worthy of death, apparently on the allegation of complicity with Jesus in working to deceive the people.

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free