The Know

After four introductory chapters, the body of the Apocalypse of John begins with the Revelator seeing a book, a scroll, or document of some kind, in the hand of the Lord, who was seated upon his heavenly throne. The record was written with one part on the interior and the other part on the exterior and then had been sealed with seven seals (Revelation 5:1).1

An angel then called, “Who is worthy open the book, and to loose the seals thereof? (Revelation 5:2). Only a person with proper authority could break the seals and open the book. No worthy person was found to do this until the Lamb of God stepped forth. Recognizing Him, the people sang a new song, “Thou art worthy to take the book, and to open the seals thereof: for thou wast slain, and hast redeemed us to God by thy blood out of every kindred, and tongue, and people and nation; and hast made us unto our God kings and priests: and we shall reign on the earth” (Revelation 5:9).

One by one, the seven seals were then opened by the Lamb (Revelation 6:1–17; 8:1). When the seventh seal was opened, “there was silence,” and John was escorted by the angel into the Holy Place of the Lord’s Temple, at the place of the incense altar and its golden censer before the throne of God in the Holy of Holies, with prayers of the Saints being raised up to God (Revelation 8:1–4).

This fascinating heavenly vision continues for the rest of the book of Revelation, which ends in the “new heaven and a new earth, . . . the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven,” as the new King, God himself, come to rule and reign (Revelation 21:1–3). Jesus, the Alpha and the Omega, then bestows this gift: “I will give unto him that is athirst of the fountain of the water of life freely. He that overcometh shall inherit all things; and I will be his God, and he shall be my son” (Revelation 21:6–7).

Centuries before the Apostle John’s day, other prophets had seen a heavenly book. About 600 B.C., Lehi experienced a heavenly vision in which he was finally handed “a book” and was invited to read of the destruction of the wicked in Jerusalem and also to learn that the Lord God would “not suffer those who come unto [Him] that they shall perish!” (1 Nephi 1:11–14). Thirty years into the captivity of the Judeans in Babylon, Ezekiel also beheld a vision. He wrote: “And when I looked, behold, an hand was sent unto me; and lo, a roll of a book [a scroll] was therein; and he spread it before me; and it was written within and without: and there was written therein lamentation, and mourning, and woe” (Ezekiel 2:9–10). In both of these cases, as was also the case for John, the prophet could not read the book until someone with authority opened it and allowed him to read.

Although the books or scrolls shown to Lehi and Ezekiel were not said to be sealed, the common practice in the ancient world was for official and legal records to be “sealed.” Seals were stamps or cylinders that could be impressed onto clay or wax, attached by a string or envelope enclosing the document to protect it from damage or from falling into the hands of someone who was not supposed to know its contents.2 Evidence of this widespread legal practice is found in Jeremiah 32:6–16, when the prophet Jeremiah purchased some family land from his nephew. This was about the same time as Lehi, which may account for a similar doubled, sealed, witnessed documentary pattern in 2 Nephi 27:12, 14 (“witnesses”), 15 (part “not sealed”), and 17 (part “sealed”).

To make such a transaction binding, the text of the contract (or covenant) was written on a papyrus page first on its top half and then the text was written a second time on the bottom half. The top half was then cut partially, folded into the center, rolled down, tied shut with a string, and the seals of the legal witnesses were then affixed. The top thus became the sealed text. The bottom half was then also folded and rolled up, and the entire bundle was then tied and closed again, but it could be opened and consulted by the parties to the deal. Jeremiah’s text that was not clearly understood until examples of such Hebrew legal texts were discovered at Elephantine in Egypt.3

Greek parchments found during the excavation of the fourth century B.C. Syrian city Dura-Europos are evidence of the Jewish practice of doubled legal documents written on leather. Jewish law prescribed in detail how these doubled, sealed, and witnessed documents should be configured in order to qualify as valid legal records. Talmudic law required three witnesses in order to make the document indisputable. In the case of dispute over the contents of the contract, a judge could break the seals and unroll the sealed top half of the document, in order to be certain of the wording of the document.

Several legal systems in the ancient world used doubled (duplicated) documents to back up and to preserve important texts. Doubled, sealed, and witnessed documents are found written in Akkadian (by the Babylonians), Hebrew (Israelites), and Greek and Latin (Greeks and Romans), on clay tablets, papyrus and parchment scrolls, wooden tablets, and metal plates. The Babylonians, as early as 2000 B.C., used such a system in writing legal contracts, deeds, and business transactions. Scribes wrote up the transactions in cuneiform on clay tablets, many of which are still legible.

Witnesses would roll a personal seal onto the wet clay of a document before it dried. The tablet was then wrapped in an “envelope” formed by a thin sheet of clay with the text repeated on the outside clay as well. Finally, the witnesses impressed their seals on the outer portion. Only a judge or authorized party could, at a later time, legally open the outer envelope to compare the inner sealed text. This practice made forgery or alteration virtually impossible, because multiple witnesses were involved and because both tablets had to dry together to prevent the outer envelope from cracking.

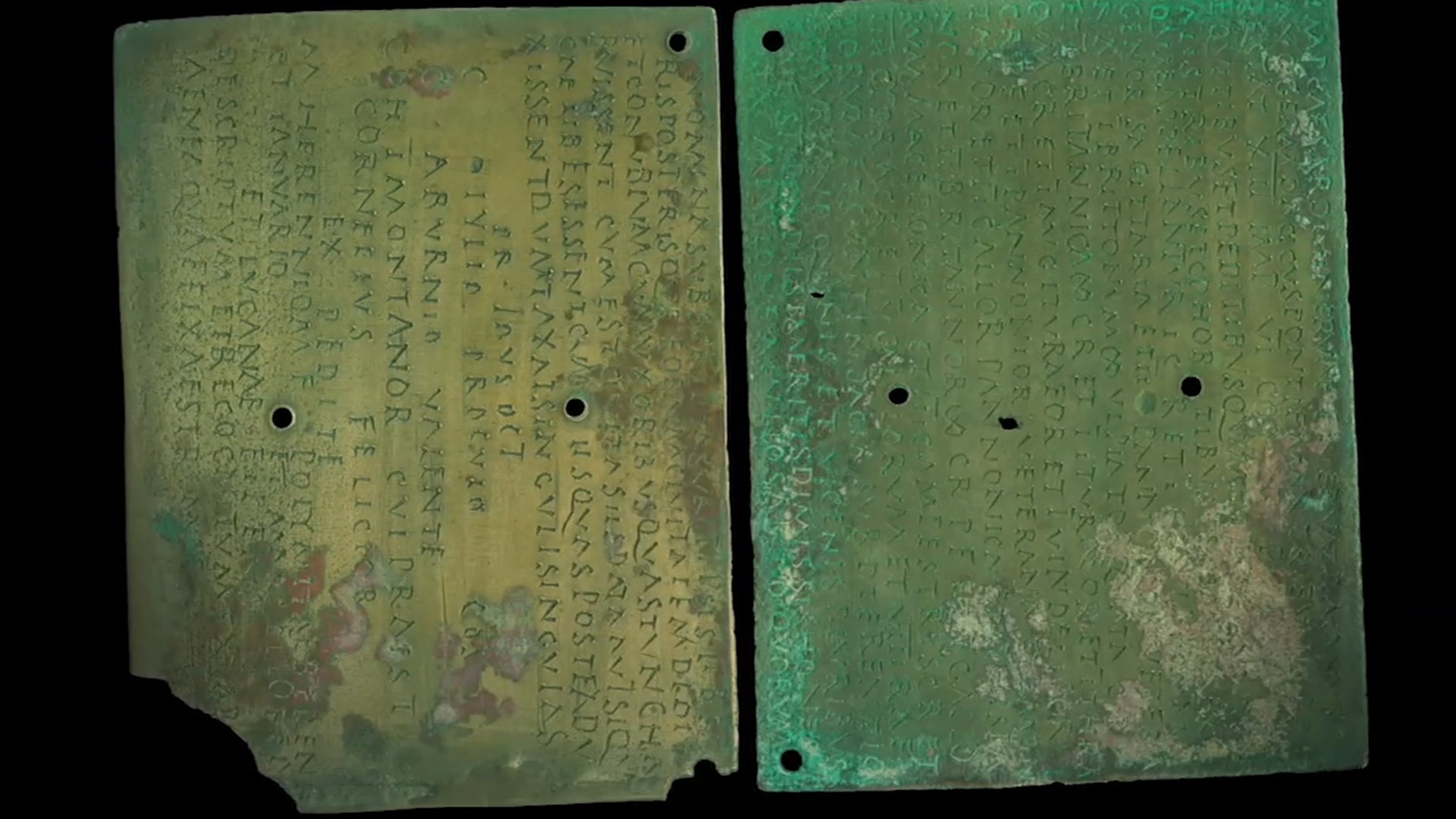

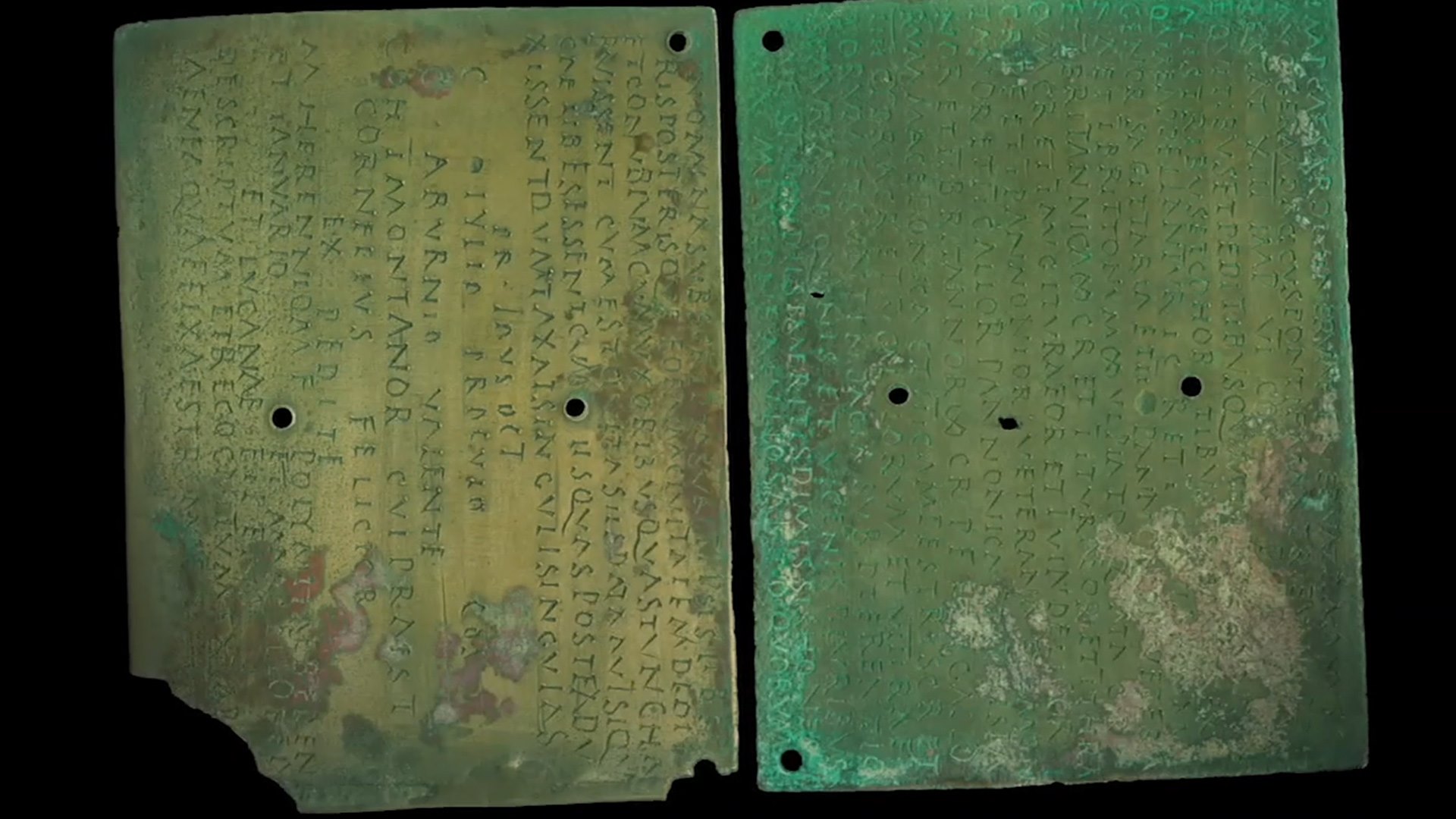

But, how many witnesses were required in such cases? For people who puzzle about the meaning of Revelation 5:1, a high-level Roman practice may offer some eye-opening clues. The Roman practice of awarding citizenship to retiring soldiers who had served in active duty for twenty-five years began around 60 A.D. and was well established by the end of the first century when the Revelation of John was written. This grant of citizenship, the most powerful status in Roman society, was awarded by imperial officials, who handed the recipient a matched pair of two bronze plates. Only a judge could open these plates, should there be any question about the validity of the rights and privileges granted by this official document.4

The text was written twice: once on the outside of the first plate, and a second time on the inner surfaces of plate 1 and plate 2. On the backside of plate 2, the names of seven Roman officials were written, and their seven seals were affixed to the plates that were bound together with a sealing wire that ran through the center of the two plates and was twisted and covered with sealing wax on the back. Two small copper rings were placed in the side corners, so the plates could be opened like a book once the sealing wire had been removed.5 These two plates were called a “diploma” (plural, diplomata), which is a Latin word for a document of recommendation for people traveling to the provinces. The word was borrowed from the Greek word simply meaning “doubled” or “folded” (diplōnō), as these documents were doubled.

More than 48 relatively complete sets of Roman plates have survived, ranging from 64 A.D. until the fourth century, when the practice ceased. With only one exception, seven was the number of official witnesses required by Roman law and practice in every known case.6 This prestigious, formal practice would certainly have been familiar to many people throughout the Roman Empire in John’s day. His revelation was received on the island of Patmos, off the coast of Turkey, not far from Ephesus, the capital of the very influential Roman province called Asia.

One might well wonder why John’s revelation might have mentioned this Roman practice in such specificity. There may be several reasons why.

The Why

This unusual piece of John’s revelation would certainly get people’s attention. It would have been a familiar but distinctive practice, signaling to readers that something very formal, important, and valuable was to about to be disclosed, announced and bestowed.

This usage would have appealed to everyone, whether Roman, Jewish, or otherwise. To a Roman, it would have signaled propriety and dignity. To people of Jewish backgrounds, it would have reminded them of scriptural passages and customary practices. To others, it would have been inclusive, since it was through diplomata that people of any cultural origin could become full-fledged Roman citizens, being no more strangers or foreigners.

This formality signaled binding legality. With this entrée, the heavenly book is presented as documentary evidence of a legal covenant between God and the world. While earthly documents are binding on earth, this revealed book is set forth as being even stronger than they are. What the heavenly book offers and binds is bound both in heaven also on earth.

Just as seven official seals were required to make Roman diplomata valid, God’s covenant is authenticated and held inviolate by seven majestic seals. God’s eternal plan and determinate decree are herewith signed, sealed, and now delivered.

Only an authorized judge or official could open any such doubled, sealed document. The book of Revelation emphasizes that Jesus Christ alone held the authority, not only on earth but also in heaven, to open the seals and to allow others to know its contents (Revelation 5:9).

In addition, Roman diplomata served the special function of granting citizenship to soldiers who had fought valiantly for twenty-five years. Each diploma recounted all the locations and units in which the retiring soldier had served. Citizenship was the coveted prize awarded for true and faithful service. So too, the Revelation of John welcomes its faithful followers as citizens in the New Jerusalem, the holy city of God, in recognition of the battles fought and the victory won against Satan and his minions.

In a Roman setting, citizenship rights were also given to the sons and daughters of the honored soldier. They too will be blessed as heirs, as if they had been born to a Roman father. Inheritance of property rights was important, especially among Roman and Jewish populations. This too would be anticipated in the opening of the seventh seal of the heavenly book, where the person who conquers the foe of evil will “inherit all things” and will be rewarded as a son of God (Revelation 21:7), having a place in the fruitful and templed land of the blessed (Revelation 21:10–22:5). Likewise. Roman wills also had to be sealed with the seals of seven witnesses, and their terms could not be executed until all seven seals were officially broken and the document opened.7

And thus, this auspicious beginning might even have been so singularly powerful as to seem disruptively countercultural to some. By co-opting a Roman imperial prerogative to make such military awards and bequests, the Revelation of John, thereby—and this would not have been unintentional—testifies that Jesus and His Father are more powerful than any other gods or beings, including the deified Emperor himself.

Further Reading:

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would a Book Be Sealed? (2 Nephi 27:10),” KnoWhy 53 (March 14, 2016).

John W. Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents: From the Ancient World to the Book of Mormon,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1998), 391–444.

John W. Welch and Kelsey D. Lambert, “Two Ancient Roman Plates,” BYU Studies 45, no. 2 (2006): 54–76.

Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes, The Revelation of John the Apostle (Provo: BYU Studies, 2013), 146–151.

- 1. For commentary on Revelation 5:1–7, see Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes, The Revelation of John the Apostle (Provo: BYU Studies, 2013), 146–151.

- 2. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would a Book Be Sealed? (2 Nephi 27:10),” KnoWhy 53 (March 14, 2016).

- 3. See generally John W. Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents: From the Ancient World to the Book of Mormon,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1998), 391–444.

- 4. See John W. Welch and Kelsey D. Lambert, “Two Ancient Roman Plates,” BYU Studies 45, no. 2 (2006): 54–76.

- 5. Welch and Lambert, “Two Ancient Roman Plates,” 56–59.

- 6. The one exception, and also the earliest instance, had eight witnesses. This data has been collected from the technical reports published by Margaret M. Roxan, and Paul Holder, Roman Military Diplomas, I–V (London: Institute of Archaeology and Classical Studies, 1978–2006).

- 7. See R. H. Charles, Critical and Exegetical Commentary of the Revelation of St. John (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920), 1:137–38, cited in Draper and Rhodes, Revelation of John the Apostle, 148.