The Know

The Zoramites denied the need for the Atonement (Alma 31:16–17). Hence, when preaching in their city, Amulek stressed the importance of “a great and last sacrifice,” a sacrifice which, he said, “must be an infinite and eternal sacrifice” (Alma 34:10). Amulek went to great lengths to explain what this sacrifice—the Atonement—was not: “not a sacrifice of man, neither of beast, neither of any manner of fowl; for it shall not be a human sacrifice” (v. 10).1 This clarification likely reflects specifically ways in which the Zoramites had “pervert[ed] the ways of the Lord in very many instances” (v. 11).

Both the Israelites and Nephites lived among cultures that performed vicarious sacrifices for the sins of individuals and communities. Jewish Studies lecturer, Dr. Elaine Goodfriend, explained, “Vicarious punishment—when the penalty for a wrong is suffered by someone other than the perpetrator—is found in” some Mesopotamian laws.2 Ze’ev Falk noted, “in Babylonian and perhaps also in Hittite law, the principle of talion was applied not only to the criminal himself but also to his dependents.”3

In contrast to some practices of their neighbors, Israelite law did not allow for vicarious punishment, but insisted “every man shall be put to death for his own sin” (Deuteronomy 24:16; cf. Ezekiel 18:20).4 Similarly, Amulek asked the Zoramites, “Now, if a man murdereth, behold will our law, which is just, take the life of his brother?” The answer was straightforward: “there is not any man that can sacrifice his own blood which will atone for the sins of another” (Alma 34:11).

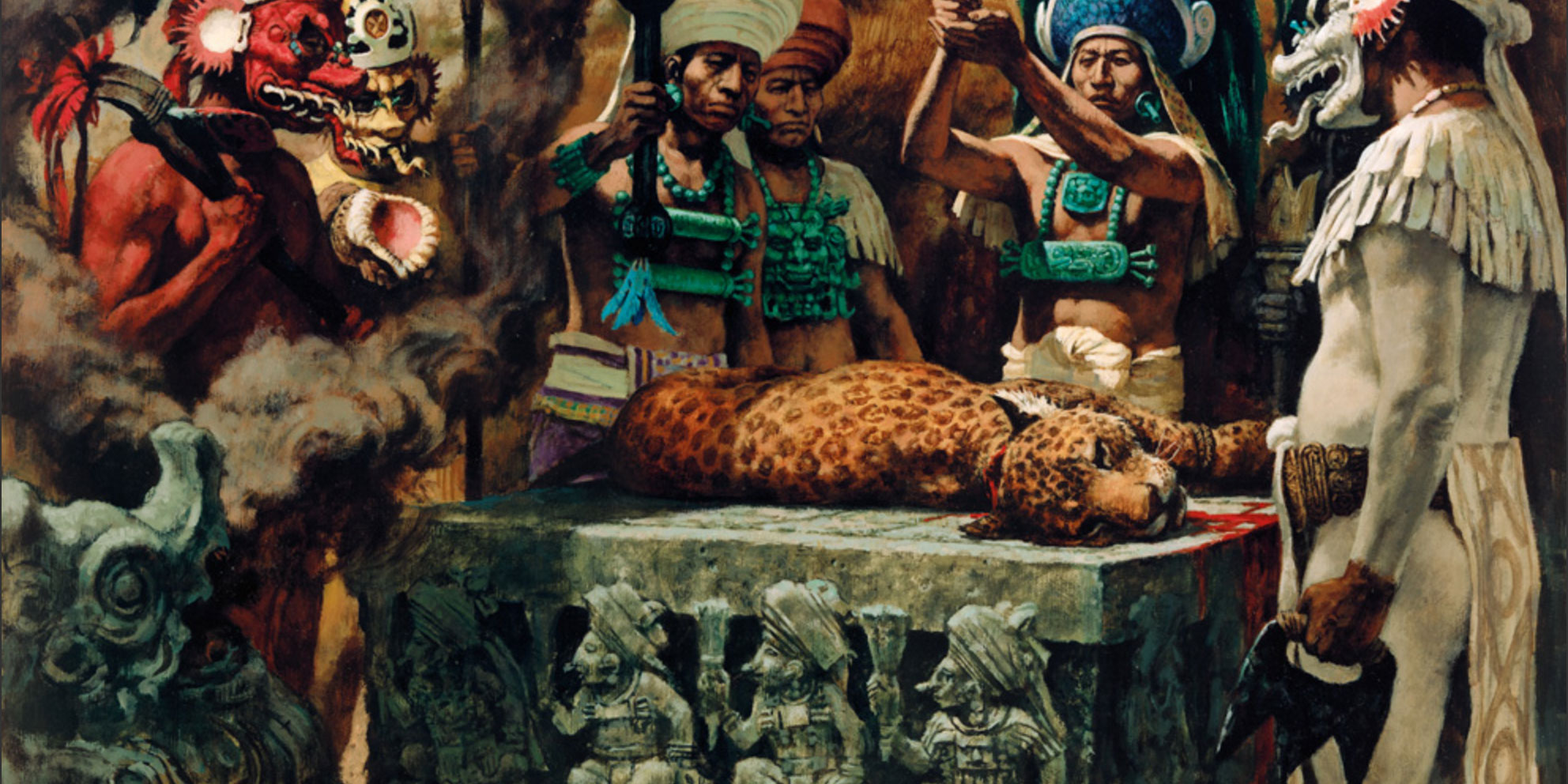

In their divergent state of apostasy, the Zoramites may thus have adopted some kind of religious system which practiced vicarious blood sacrifices. Ancient Mesoamerica provides a potential cultural backdrop. There, “Maya kings voluntarily shed their blood as an offering on behalf of their people.”5 This came in the form of bloodletting, a practice where the king “used thorns, stingray spines, and obsidian blades to draw blood from” sensitive parts of the body.6 While this is a different conceptual background than that of the Babylonian laws in the Old World, it was still a system wherein a man would “sacrifice his own blood” vicariously for his people.7

There were also other forms of sacrifice practiced in Mesoamerica. Brant A. Garnder explained, “Mesoamerican culture also offered parallel examples of animal sacrifices as part of their worship and even human sacrifice.”8 Mark Alan Wright reasoned, “The peoples of the Book of Mormon would have been familiar with the types of sacrifices being offered by their surrounding Mesoamerican neighbors, which often comprised burnt offerings of animals, such as deer or birds.”9

Amulek explained, “For it is expedient that there should be a great and last sacrifice; yea, not a sacrifice of man, neither of beast, neither of any manner of fowl; for it shall not be a human sacrifice; but it must be an infinite and eternal sacrifice” (Alma 34:10). Wright noted, “It is significant that the three things that Amulek is expressly telling the apostate Zoramites not to sacrifice are the three most common things that were offered by Mesoamerican worshipers: human, beast, and fowl.”10

Micah, an Israelite prophet, also apparently mentioned these three forms of sacrifice. He asked if he should “come before the Lord” with “burnt offerings, with calves of a year old?” Whether “the Lord [would] be pleased with thousands of rams” or if he should “give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?” He answered, “the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God” (Micah 6:6–8).

Recognizing that birds were often given as “burnt offerings,” Amulek seems to be reversing the order of Micah’s rhetorical questions, after which he launches into an exposition of justice and mercy (Alma 34:15–16). Amulek, therefore, seems to be employing a technique called Seidel’s Law to invoke Micah’s words and remind his Zoramite audience of the true purpose of animal sacrifice under the Mosaic law.11

The Why

As pious Israelites, the Nephites would have practiced various forms of animal sacrifice as part of the law of Moses. They did so, however, with an awareness that such sacrifices were only a type and a shadow, “every whit pointing to that great and last sacrifice … [of] the Son of God, yea, infinite and eternal” (Alma 34:14). In the Nephite view, “The law of Moses was as one grand prophecy of Christ inasmuch as it testified of the salvation to be obtained in and through his atoning blood.”12

In their apostasy, the Zoramites rejected the infinite and eternal atonement of Jesus Christ. Influenced by the surrounding culture, it seems they instead treated animal sacrifice as a full substitute for the Atonement, perhaps going so far as to have adopted other local sacrificial customs, such as bloodletting and human sacrifice.

Amulek, therefore, made it a point to explain that “there is not any man that can sacrifice his own blood” on behalf of others (Alma 34:11), as would be the case with even a king while bloodletting. Nor could any kind of blood sacrifice—beast, fowl, or human—cleanse the Zoramites, nor anyone else, of their sins (vv. 11–14). Not only does logic work against the Zoramite view, but so did the symbolism of the law of Moses which prohibited the taking of one mortal life in punishment for the wrongdoing of another.

For any sacrifice to have eternal force and effect, that sacrifice must be more than mortal and temporary. Elder Tad R. Callister explained:

The word infinite, as used in this context, may refer to an atonement that is infinite in its scope and coverage, … to an atonement that simultaneously applies retroactively and prospectively, oblivious to constraints and measurements of time … to an atonement that applies to all God’s creations, past, present, and future, and thus is infinite in its application, duration, and effect.13

“Nothing short of the shedding of the blood of both an infinite and perfect Being could”14 accomplish this kind of ever-enduring and all-reaching sacrifice. “Accordingly,” explained Callister, “the Atonement is ‘infinite’ because its source is ‘infinite’.”15

Just as certain particular cultural factors apparently had enticed the Zoramites to pervert the ways of the Lord, so also may social trends today entice some to twist, distort, wrest, or otherwise skew true gospel principles to fit fashionable ideologies. Avoiding these temptations requires both individuals and communities to do as Alma taught, and Amulek reiterated: “plant the word in your hearts, that ye may try the experiment of its goodness” (Alma 34:4). Only by letting the eternal word of Christ take root can the everlasting Gospel then become the guiding light which enables all to see past the temporary fashions of the day.

Further Reading

Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 25–55.

Rodney Turner, “The Infinite Atonement of God,” in Book of Mormon, Part 2: Alma 30 to Moroni, Studies in Scripture: Volume 8 (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988), 28–40.

- 1. Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 52: “Perhaps we are seeing clues to the process of apostasy when Amulek is teaching Zoramite outcasts and specifically defines Christ’s sacrifice by what it was not.”

- 2. Elaine Adler Goodfriend, “Ethical Theory and Practice in the Hebrew Bible,” in The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Ethics and Morality, ed. Elliot N. Dorff and Jonathan K. Crane (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013), 48 n.9. Goodfriend specifically cited “the Laws of Hammurabi 230 and 210, and Middle Assyrian Law A55.”

- 3. Ze’ev W. Falk, Hebrew Law in Biblical Times, 2nd ed. (Winona Lake, IN and Provo, UT: Eisenbrauns and BYU Press, 2001), 68. Talion is the “eye for an eye” concept, or in the case of murder, a life for a life. Talionic justice and the Book of Mormon will be further discussed in Book of Mormon Central’s “Why and How Did Alma Explain the Meaning of the Word ‘Restoration’? (Alma 41:1),” KnoWhy 149 (July 22, 2016).

- 4. Falk, Hebrew Law, 68 noted, “Hebrew courts did not inflict punishment on ascendants or descendants,” and Goodfriend, “Ethical Theory,” 48 n.9, in relation to vicarious punishment, noted “Exod 21:31 and Deut 24:16 prohibit this practice.”

- 5. Wright and Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 51.

- 6. Wright and Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 51. See Mary Miller and Karl Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (London, Eng.: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 42, 46–47; Arthur Demarest, Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 184–188. Michael D. Coe and Stephen Houston, The Maya, 9th edition (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 2009), 89, noted bloodletting is depicted at San Bartolo, dating to ca. first or second century BC. They also mention the attestation of bloodletters from Olmec times. Robert J. Sharer with Loa P. Traxler, The Ancient Maya, 6th edition (Stanford, CA: Standford University Press, 2006), 197 described “a lavish ritual involving feasting, bloodletting, and burning incense” from “the end of the Middle Pre-Classic,” ca. 800–500 BC. So bloodletting seems clearly attested in Book of Mormon times. Also see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does King Benjamin Emphasize the Blood of Christ? (Mosiah 4:2),” KnoWhy 82 (April 20, 2016).

- 7. Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:478: “Amulek says ‘sacrifice his own blood’ because the king’s letting of some of his own blood was ‘the mortar of ancient Maya ritual life.’”

- 8. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:477, typo silently corrected.

- 9. Mark Alan Wright, “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 12 (2014): 89. Also see Miller and Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, 96–97, 144–146.

- 10. Wright, “Axes Mundi,” 89.

- 11. Micah askes about burnt offerings (usually birds), then calves and rams, and then his firstborn, thus providing a sequence of fowl, beast, man. Amulek reverses in stressing it will not be man, beast, or fowl. This kind of reversal is what scholars call Seidel’s Law. See David Bokovoy, “Inverted Quotations in the Book of Mormon,” Insights: A Window on the Ancient World 20/10 (October 2000): 2; David E. Bokovoy and John A. Tvedtnes, Testaments: Links Between the Book of Mormon and the Hebrew Bible (Tooele, UT: Heritage Press, 2003), 56–60.

- 12. Robert L. Millet and Joseph Fielding McConkie, Doctrinal Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1897–1992) 3:250.

- 13. Tad R. Callister, The Infinite Atonement (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000), 59.

- 14. D. Kelly Ogden and Andrew C. Skinner, Verse by Verse: The Book of Mormon, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2011), 2:18.

- 15. Callister, The Infinite Atonement, 58. Callister went on to write: “Why was it essential that the Atonement be performed by Jesus, who is “infinite and eternal” (Alma 34:14)? Because the Atonement required power, incredible power, even infinite power. … Such power could be exercised only by a being who was infinite, meaning a being who possessed all divine virtues in unlimited measure, and was therefore a God” (p. 67).