The Know

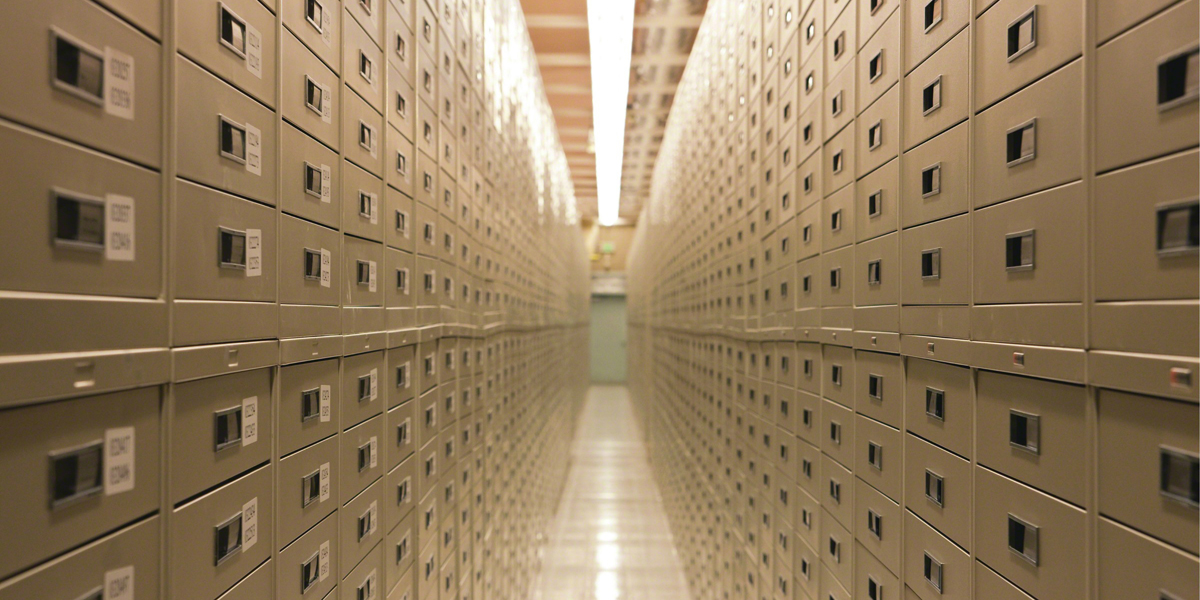

In 1831, John Whitmer became the first official LDS church historian.1 He received this calling in a formal revelation, which stated that he should “keep a regular history” of the church and that it should be kept “continually” (Doctrine and Covenants 47:1, 3). With varying degrees of success,2 Whitmer and other early Saints made efforts to comply with this divine commandment. They kept personal journals, recorded sermons, took notes during meetings, recorded priesthood ordinances and blessings, and collected reports of the persecution of their people (see Doctrine and Covenants 123:1–7).3

The importance of record keeping was further highlighted when Joseph Smith introduced the doctrine of baptisms for the dead.4 In a letter regarding vicarious ordinances, he instructed record keepers to take “accurate minutes” and to “be very particular and precise in taking the whole proceedings, certifying in his record that he saw with his eyes, and heard with his ears, giving the date, and names, and so forth” (Doctrine and Covenants 128:3). The prophet explained that whenever God’s people have acted “in authority, in the name of the Lord, and did it truly and faithfully, and kept a proper and faithful record of the same, it became a law on earth and in heaven, and could not be annulled” (v. 9).

Book of Mormon prophets can surely be counted among the righteous Saints who have “kept a proper and faithful record” of important revelations and events.5 They cherished their own sacred records, particularly the brass plates, because these writings had “enlarged the memory of [their] people, yea, and convinced many of the error of their ways” (Alma 37:8).6 In their concern for future generations, they continued the tradition of writing on metal plates because they knew that “whatsoever things we write upon anything save it be upon plates must perish and vanish away” (Jacob 4:2).7

More than that, the Nephite prophets kept careful records because the Lord explicitly commanded them to do so, often without their knowing why. Nephi, for example, wrote that the Lord commanded him to make his small set of plates “for a wise purpose in him, which purpose I know not” (1 Nephi 9:5).8 Mormon similarly said that although he did “not know all things,” he included certain records “for a wise purpose; for thus it whispereth me, according to the workings of the Spirit of the Lord which is in me” (Words of Mormon 1:7).

Like the various types of record keeping among the early Saints, the Book of Mormon was composed from a variety of different records. These include items such as letters, military histories, accounts of leaders or heroes, political histories, migration histories, recorded ceremonies, prophecies, year counts and calendrical histories, annals, tax or tribute lists, genealogies, and lineage histories.9 Without the details, both sacred and ordinary, from these records, Mormon would have had little to draw upon to present the history of his people to modern audiences. Their preservation was essential to the composition of the Book of Mormon.

The Why

Records make it possible to hear the voices of peoples from the remote past and to speak to audiences in the distant future. Nephi declared that his people would “speak unto [future generations] out of the ground” and that their “speech shall whisper out of the dust” (2 Nephi 26:16). In this way, records are able to link generations of people together that would otherwise be far apart. As Elder Richard G. Scott described it, the scriptures—and by implication the prophets who wrote them—can become “stalwart friends that are not limited by geography or calendar.”10

“Record Keeping,” explained Anita Wells, “is of more than merely historical interest; it has eternal significance and consequences.”11 When the Savior was among the Nephites, He taught that “out of the books which have been written, and which shall be written, shall this people be judged,” as well as the entire “world” (3 Nephi 27:25–26). This indicates that because of its divine authority, the Book of Mormon is truly a binding record,12 and we will be judged for how we respond to its truths.13

Like Book of Mormon prophets, we also have a responsibility to record and preserve our sacred experiences, both for ourselves and for future generations. Elder Scott taught, “Inspiration carefully recorded shows God that His communications are sacred to us. Recording will also enhance our ability to recall revelation. Such recording of direction of the Spirit should be protected from loss or intrusion by others.”14

Future generations will surely want to know what it has been like to live in the “eleventh hour” before Christ’s second coming (Doctrine and Covenants 33:3). Therefore, like Nephi and Mormon, we should follow spiritual promptings to record sacred events and truths, even if we can’t immediately discern God’s purposes for having us do so. It also wouldn’t hurt to record some of the more everyday particulars of our lives. Sometimes these details provide important context for our more sacred moments, just like the various types of Book of Mormon records provided the needed background to make sense of its stories.

Through sacred records, God’s children from different places and times can have their “hearts knit together in unity and in love one towards another” (Mosiah 18:21). As we diligently study the sacred records of past peoples and dispensations, our hearts will turn to them in gratitude. And as we preserve our own sacred records for future generations and posterity, we will look forward with charity and hope for God’s blessings to rest upon them. In the end, God will honor the faithful records of priesthood ordinances kept by His people, and like a “welding link,” these authorized blessings will bind us together for eternity (Doctrine and Covenants 128:18).15

Further Reading

Anita Wells, “Bare Record: The Nephite Archivist, The Record of Records, and the Book of Mormon Provenance,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 99–122.

Matthew McBride, “Letters on Baptisms for the Dead,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), online at history.lds.org.

John L. Sorenson, “Mormon’s Sources,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 2 (2011): 2–15.

Louis Midgley, “The Book of Mormon as Record,” FARMS Review 21, no. 1 (2009): 45–51.

“Journals: Of Far More Worth than Gold,” in Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Wilford Woodruff (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004), 125–133.

- 1. John Whitmer replaced Oliver Cowdery who, since the organization of the church in 1830, had been unofficially keeping church records. In the revelation, the Lord explained that Whitmer was being called to the position because “Oliver Cowdery I have appointed to another office” (Doctrine and Covenants 47:3).

- 2. See Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York, NY: Knopf, 2005), 233.

- 3. See Howard C. Searle, “Historians, Church,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 2:589–592.

- 4. See Matthew McBride, “Letters on Baptisms for the Dead,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), online at history.lds.org.

- 5. See Louis Midgley, “The Book of Mormon as Record,” FARMS Review 21, no. 1 (2009): 45–51.

- 6. The blessings of Nephite record keeping can be contrasted with the plight of the Mulekites, whose “language had become corrupted” and who “denied the being of their Creator” because they “brought no records with them” (Omni 1:17).

- 7. For a general treatment of writing on metal plates in the ancient world, see William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54; H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents of Antiquity,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 10, no. 4 (1970): 457–477. See also, Book of Mormon Central, “What Kind of Ore Did Nephi Use to Make the Plates? (1 Nephi 19:1),” KnoWhy 22 (January 29, 2016).

- 8. Nephi’s small plates would offer a divine solution to the 116 pages lost by Martin Harris. Elder Kim B. Clark explained, “Without Lehi’s record [which was lost with the 116 pages], there would be no account of Lehi’s family, the journey to the promised land, or the origin of the Nephites and Lamanites. In May of 1829 the Lord revealed to Joseph a plan, centuries in the making, to replace the book of Lehi with what we now know as the small plates of Nephi.” Kim B. Clark, “Thou Art Joseph,” Worldwide Devotional for Young Adults, May 7, 2017, online at lds.org.

- 9. See John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 187–198. See also John L. Sorenson, “Mormon’s Sources,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 2 (2011): 2–15; Brant A. Gardner, “Mormon’s Editorial Method and Meta-Message,” FARMS Review 21, no. 1 (2009): 83–105; Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), xv; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Were Genealogies Important to Book of Mormon Peoples? (Jarom 1:1),” KnoWhy 76 (April 12, 2016).

- 10. Richard G. Scott, “The Power of Scripture,” Ensign, November 2011, 6, online at lds.org.

- 11. Anita Wells, “Bare Record: The Nephite Archivist, The Record of Records, and the Book of Mormon Provenance,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 116.

- 12. See John W. Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents: From the Ancient World to the Book of Mormon,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 391–444; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would a Book Be Sealed? (2 Nephi 27:10),” KnoWhy 53 (March 14, 2016).

- 13. See Ezra Taft Benson, “The Book of Mormon—Keystone of Our Religion,” Ensign, November 1986, online at lds.org.

- 14. Richard G. Scott, “How to Obtain Revelation and Inspiration for Your Personal Life,” Ensign, May 2012, 46, online at lds.org. Wilford Woodruff, whose personal journal has become an indispensable record of church history, similarly taught, “Should we not have respect enough to God to make a record of those blessings which He pours out upon us and our official acts which we do in His name upon the face of the earth? I think we should.” Journal of Wilford Woodruff, February 12, 1862, as cited in “Journals: Of Far More Worth than Gold,” in Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Wilford Woodruff (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004), 129.

- 15. See also, Book of Mormon Central, “Why Will God Turn the Hearts of the Fathers to the Children? (3 Nephi 25:6),” KnoWhy 219 (October 28, 2016).