The Know

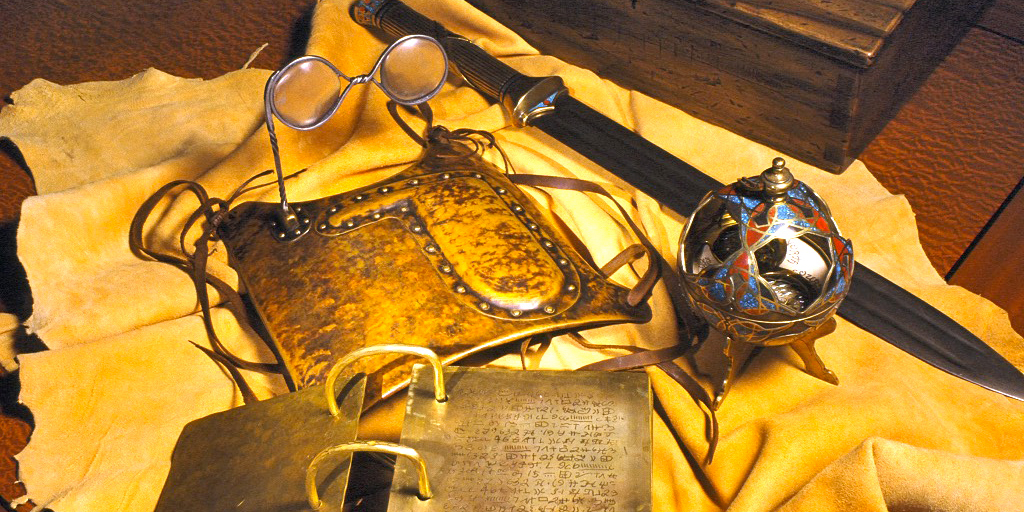

Mosiah 21 records how King Limhi sent a small expeditionary force from the land of Nephi to find the land of Zarahemla to the north. The expedition team got lost, and ended up instead finding some Jaredite ruins that included “a record of the people whose bones they had found” engraved on “plates of ore” (Mosiah 21:27). The search party returned with this record and sent it to Limhi for inspection. Because he was evidently unable to read the ancient records himself, the text indicates that “Limhi was again filled with joy on learning from the mouth of Ammon that king Mosiah had a gift from God, whereby he could interpret such engravings” (Mosiah 21:28).

While editions of the Book of Mormon since 1837 have read that king Mosiah had the divine gift of interpretation or translation, in the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon this passage reads that king Benjamin was the one with the gift. According to Royal Skousen, “the 1837 edition [of the Book of Mormon] made the change from Benjamin to Mosiah to avoid [an] apparent contradiction,” as Mosiah 6:4–5 indicates that Benjamin died three years after Mosiah became king, and since it was Mosiah, not Benjamin, who sent Ammon to search for the people of Zeniff (of whom Limhi was a descendent).1 Skousen observed, “Presumably, this emendation [in the 1837 printing] was made by Joseph Smith, although the change is not marked in the printer’s manuscript,” and so it is impossible to tell for certain who made that change.2 After examining all the evidence, Skousen’s Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text returns the reading in Mosiah 21:28 to “Benjamin.”

Complicating matters further is the fact that Ether 4:1 in the 1830 edition likewise reads that it was King Benjamin, not Mosiah, who did not allow the revelations given to the Brother of Jared to be made public in his day. This reference to Benjamin likewise was changed in 1849 by Orson Pratt to read “Mosiah,” apparently to keep the text consistent with Joseph Smith’s 1837 emendation.3 “The occurrence of Benjamin instead of Mosiah” originally in these passages “cannot be readily explained as an error in the early transmission of the text,” Skousen insists.4Readers are thus left with these seeming contradictions in the Book of Mormon’s narrative that Joseph Smith and Orson Pratt sought to resolve by adjusting the text.

However, people have continued to wonder. Perhaps the name Benjamin in these two passages isn’t really problematic. Hugh Nibley was one of the first to suggest that Benjamin and his son Mosiah both had access to the Jaredite records, and so Nibley asked: “Was it necessary to change the name of Benjamin (in the first edition) to Mosiah in later editions of Ether 4:1?” Nibley goes on:

Probably not, for though it is certain that Mosiah kept the records in question, it is by no means certain that his father, Benjamin, did not also have a share in keeping them. It was Benjamin who displayed the zeal of a life-long book lover in the keeping and studying of records; and after he handed over the throne to his son Mosiah he lived on and may well have spent many days among his beloved records. And among these records could have been the [twenty-four] Jaredite plates, which were brought to Zarahemla early in the reign of Mosiah when his father could still have been living (Mosiah 8:9–15).5

In retaining the name Benjamin, Skousen followed Nibley's suggestion reasoning that, “King Benjamin could have still been alive when the people of Limhi arrived in the land of Zarahemla, and he could have later had access to the records, including the Jaredite record.” In other words, the issue may boil down to a matter of how to read the Book of Mormon’s chronology. “Prior to his death, king Benjamin still had access to the records, and the Lord could have told him that the prophesies in those records were not to be revealed at that time.”6 If this is so, then Joseph Smith’s 1837 and Orson Pratt’s 1849 textual emendations would be unnecessary.

Also supporting the retention of the name Benjamin, Brant A. Gardner suggested another explanation. Instead of Benjamin having access to the Jaredite records at the same time as his son Mosiah, Gardner theorizes that Mormon, in abriding the record of Limhi’s people, perpetuated an error in that underlying record that Benjamin was the king being spoken of instead of Mosiah.

The people of Limhi would remember only Benjamin, their first leader, Zeniff, having departed during Benjamin’s reign (Omni 1:24–29). The recorders for Limhi’s records entered their own idea of who the unnamed king was and wrote Benjamin into the record. Mormon used that record and therefore that name.7

This would in turn explain how Moroni, “a dependent witness” who “simply uses the information as it appeared in his father’s text,” confused the name as well as he composed the book of Ether.8 If Gardner is correct, then Joseph Smith’s 1837 emendation could be seen as a prophetic correction to an error in Limhi’s report that was simply not corrected by Mormon.

The Why

In puzzling over the reading or meaning of any difficult text in scripture, it is helpful to know that not all questions cannot be answered. In most historical or ancient textual studies, conclusive data rarely exists. Sometimes it is sobering or even painful to admit that we do not know as much as we would like to know.

After identifying all of the previously proposed solutions, and considering even new information, various resolutions can be entertained. Some explanations will strike people as being more or less plausible than others, and a prevailing consensus may emerge. Even at that, a definitive answer to the question may evade us. However, while a definitive answer to this question remains elusive, readers need not abandon confidence in the Book of Mormon's credibility, especially after only a surface-level look at the issue.

Readers are better served by probing deeper into the Nephite record to try and discern insights that may have been overlooked. Instead of becoming a stumbling block for faith, wrestling with apparent contradictions such as the question of which Nephite king translated the Jaredite records in Mosiah 21:28 may, paradoxically, lead to greater confidence in and appreciation for the Book of Mormon.

Most of all, apparent contradictions such as this one do not detract from the Book of Mormon’s divine doctrinal messages. Even if someone makes a mistake, the authors of the Book of Mormon did not claim to be infallible or flawless.9 As Moroni himself wrote on its title page, “And now, if there are faults they are the mistakes of men; wherefore, condemn not the things of God.” Readers should therefore focus on how they can personally benefit from the profound teachings and eternal doctrines found in the Book of Mormon. Whether accomplished by Benjamin or Mosiah, the Jaredite records were translated and brought forth by the gift and power of God for us today.

Further Reading

Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon: Part 3, Mosiah 17–Alma 20 (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 1418–1421.

Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 7 (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1981), 6–7.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 3:374–376.

J. Cooper Johnson, “King Benjamin or Mosiah: A Look at Mosiah 21:28,” FairMormon.

L. Ara Norwood, “Benjamin or Mosiah? Resolving an Anomaly in Mosiah 21:28,” presentation given at the 2001 FAIR Conference.

- 1. Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon: Part 3, Mosiah 17–Alma 20 (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2006), 1418.

- 2. Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 1418.

- 3. Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 1419.

- 4. Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 1420–1421.

- 5. Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 7 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 7.

- 6. Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 1420.

- 7. Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 3:375.

- 8. Gardner, Second Witness, 3:376.

- 9. See Book of Mormon Central, “Are There Mistakes In The Book Of Mormon? (Title Page)” KnoWhy 3 (January 4, 2016).