Editor’s Note: This year marks 50 years since the discovery of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon on August 16, 1967. To celebrate this 50th anniversary, through July and August Book of Mormon Central will publish one KnoWhy each week that discusses chiasmus and its significance and value to understanding the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and other ancient literature. Be sure to check out our other KnoWhys on chiasmus and the Chiasmus Resources website for more information.

The Know

Chiasmus is a type of writing style which presents a series of key words or phrases and then repeats them in reverse order. Although this literary form appears in both ancient and modern texts written in “Greek, Latin, English, and other languages, the form was much more highly developed in Hebrew and dates to the oldest sections of the Hebrew Bible and beyond.”1

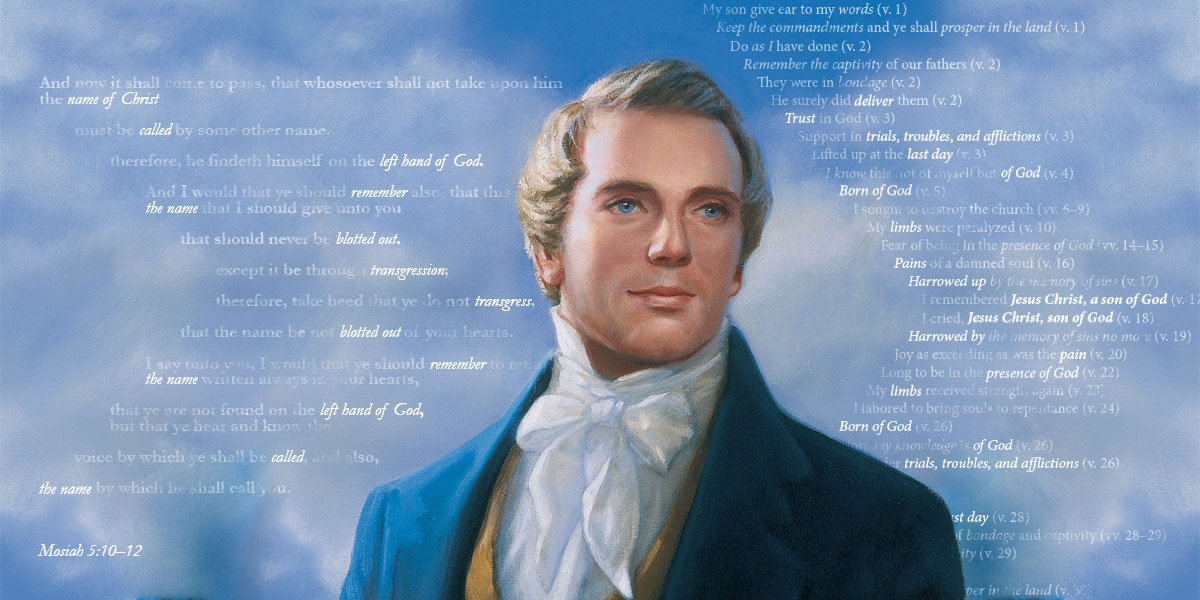

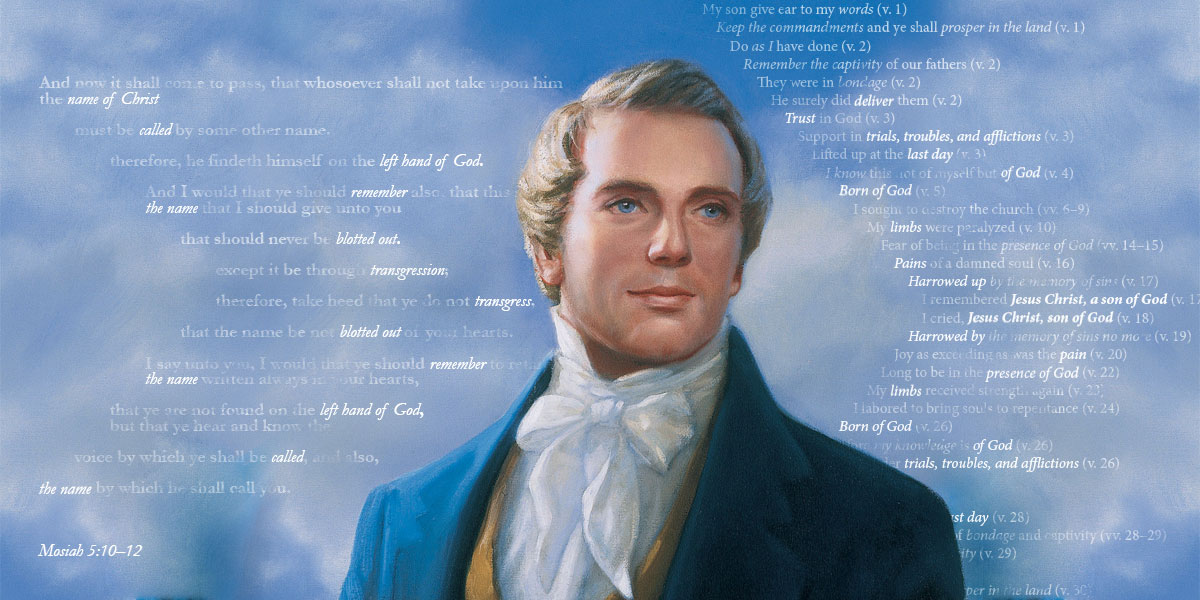

In August 1967, John Welch noticed the presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon while serving as a missionary in Germany.2 Since that time, a flood of research has been devoted to identifying and understanding its usage and importance in the Book of Mormon.3 There are now hundreds of proposed chiasms in the text,4 ranging from simple patterns, like A-B-B-A, to much more elaborate usages, such as the famous chapter-length chiasm in Alma 36.6

Many people have seen the distinctive and repeated use of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon as evidence that it was written by multiple ancient authors trained in the Hebrew literary tradition.6 Others, however, have wondered if Joseph Smith might have learned about chiasmus from biblical research available in his day.

It is true that chiasmus was not completely unheard of before 1829 when the Book of Mormon was brought forth by Joseph Smith. In 1742 German scholar D. Johannes Albertus Bengel was probably the first to apply the term chiasmus to a type of literary parallelism, which is where words and phrases on one line of writing correspond to those of another line.7 However, Bengel’s influence on other writers was minimal.8 Robert Lowth’s lectures on Hebrew poetry in 1753 at Oxford received much greater attention,9 but, according to Welch and others, Lowth apparently was "never aware of the phenomenon of chiasmus.”10

Building on the work of Lowth, John Jebb in 1820 was the first to identify chiasmus as “a distinct type of parallelism prevalent in the Old and New Testaments,”11 referring to it as epanodos.12 Reverend Thomas Boys, who was aware of Jebb’s research, then published two notable works in 1824 and 1825,13 which discussed and applied the concept of chiasmus much further.14

Although these works were potentially available to Joseph Smith, they were published in London, and the likelihood that he came across them before dictating the text of the Book of Mormon, or ever in his lifetime, seems very low. In his research on this subject over the years, Welch has found “no evidence that the 1820, 1824, or 1825 works of Jebb or Boys themselves reached America, let alone Palmyra or Harmony, in the 1820s.”15

Pages 456–457, 467 of Horne's book on Biblical studies. These pages show what a person in 1829 could have known about Chiasmus, which wasn’t very much. Images via google books.

As close as one finds is a brief summary of Jebb’s 1820 work that was included in the second, 1825 edition of Thomas Hartwell Horne’s massive introduction to the critical study of the Bible, printed both in London and Philadelphia.16 In its 28-page chapter on Hebrew poetry, there are three short examples of “parallel lines introverted” in the Old Testament and two A-B-B-A examples in the New Testament.17 As Welch also has observed, “Horne’s work is massively intimidating … [and] mentions virtually everything in the then-known world of biblical scholarship. Merely locating the discussion of chiasmus, epanodos, or introverted parallelism in this vast array is difficult, even when one knows what to look for.”18

The Why

These sources indicate that there was some knowledge of chiasmus and parallelisms in the Bible prior to the translation of the Book of Mormon in 1829. Despite Joseph Smith’s potential access to these sources, however, there is no direct evidence that he ever heard of chiasmus or came into contact with the works of Jebb or Boys before he translated the Book of Mormon. Nor did Joseph Smith himself ever describe or even mention chiasmus during his lifetime,19 even though he acquired a copy of Horne’s Introduction to the Critical Studies of the Scriptures in Kirtland, Ohio, in 1835, but by then the Book of Mormon had been in print for five years.20

This lack of any hint of awareness on his part poses a problem for the suggestion that Joseph Smith used pre-1829 research on chiasmus to help him concoct the Book of Mormon. Is it really likely that any forger would spend the time to research this complex literary form, perfect his or her mastery of it, use it in dozens of instances in his fabricated scripture, and then never once mention its presence or lead anyone to its discovery? Such a scenario seems highly unlikely.

Furthermore, Welch has argued that “even if Joseph Smith had read Horne or Jebb, he still would have known little about structural chiasmus.”21 Many of the chiasms in the Book of Mormon are highly sophisticated, and in several ways the Book of Mormon’s use of chiasmus actually varies or strays from what the early pioneers in the field were saying.22

The Book of Mormon’s overall use of chiasmus was truly ahead of its time. Or, perhaps better stated, it was behind its time—thousands of years behind. Only recent research has begun to uncover what no one saw in its pages for more than 130 years after its publication—the presence of its chiastic structures and their close match with chiasms from the ancient world.23

The overall complexity of the Book of Mormon and the miraculous nature of its translation must also be taken into consideration.24 Even if Joseph Smith had known of chiasmus, he would still have been “presented with the formidable task of writing—or rather, dictating—extensive texts in this style.”25 “Imagine the young prophet,” said Welch, speaking in a “style that was unnatural to his world, while at the same time keeping numerous other strands, threads, and concepts flowing without confusion in his dictation.’”26 Amazingly, he accomplished this without relying on any working notes or reference materials of any kind, according to witnesses who were close to the process.27

With these additional factors in mind, it is especially difficult to suppose that the many sophisticated chiasms in the Book of Mormon were simply derived from research available in 1829. On the other hand, their presence is easily accounted for if the Book of Mormon was truly written by ancient prophets who inherited the Hebrew literary tradition from their ancestors and then took great care to “preserve unto [their] children the language of [their] fathers” (1 Nephi 3:19).28

Further Reading

John W. Welch, “The Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon: Forty Years Later,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 74–87, 99.

John W. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829 When the Book of Mormon Was Translated?” FARMS Review 15, no. 1 (2003): 47–80.

John W. Welch, “What Does Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Prove?” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1996), 199–224.

- 1. John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982; reprinted by FARMS, 1996), 34.

- 2. See John W. Welch, “The Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon: Forty Years Later,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 74–87, 99.

- 3. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why is the Presence of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Significant? (Mosiah 5:10–12),” KnoWhy 166 (August 16, 2016).

- 4. Donald W. Parry, Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon: The Complete Text Reformatted (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2007), 565. See also “Chiasmus Index, Book of Mormon,” at Chiasmus Resources, online at chiasmusresources.org.

- 6. a. b. See John W. Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 2 (1995): 1–14; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Alma Converted? (Alma 36:21),” KnoWhy 144 (July 15, 2016); John W. Welch, “A Masterpiece: Alma 36,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 114–131; John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in Alma 36,” FARMS Preliminary Report (1989).

- 7. See John W. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829 When the Book of Mormon Was Translated?” FARMS Review 15, no. 1 (2003): 53.

- 8. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 54. Bengel was a German scholar in Wüttemberg; his main books were written in Latin.

- 9. Robert Lowth, Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews, trans. G. Gregory (London, UK: Johnson, 1787), as cited in Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 53.

- 10. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 53. Lowth’s main work on parallelism in general is mentioned in Welch’s first publication about chiasmus, in John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 10, no. 1 (1969): 72 n. 2.

- 11. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 55.

- 12. See John Jebb, Sacred Literature (London, UK: Cadell and Davies, 1820), 335–362. Epanodos refers to a form of parallelism very similar to chiasmus and is often used instead of chiasmus in this early literature.

- 13. See Thomas Boys, Tactica Sacra (London, UK: Seely, 1824) and Key to the Book of Psalms,(London, UK: Seely, 1825).

- 14. See Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 61–63.

- 15. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 76.

- 16. In 1825, Horne published the 4th edition of his three-volume Introduction to the Critical Study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures (Philadelphia, PA: Littell, 1825). It seems to have been the first American publication to mention Jebb’s work on chiasmus. A 6th edition of this biblical encyclopedia was published in 1828, with changes mostly to its typesetting. In 1827, Horne published the 2nd edition of a condensed version of his encyclopedia, called Compendious Introduction to the Study of the Bible (New York, NW: Arthur), and in 1829 he published a 3rd edition. These works contained an even briefer mention of Jebb’s chiasmus-related writings (p. 191 in the 1827 edition and p. 144 in the 1829 edition). These encyclopedic volumes never discussed Boys’ research on chiasmus in the Psalms and in the New Testament, and it appears that only Horne’s 1825 edition was published in America. This information corrects and expands what was known in the 1960s and 1970s about these obscure sources. See Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 63–68.

- 17. Horne, Introduction to the Critical Study, 456–457, 467.

- 18. See Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 78.

- 19. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 47.

- 20. Examining this book in the Community of Christ Library in Independence, Missouri, Welch found “no evidence on any page that this copy of this book was ever read by anyone. The book is completely clean: there are no notes, no marginalia, no smudge marks, and no creased pages. It would appear that Joseph did not study this kind of reference material.” Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 78.

- 21. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 78.

- 22. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 79.

- 23. See Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” 43–51; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Nephi Use Chiasmus to Testify of Christ? (2 Nephi 11:3),” KnoWhy 271 (February 6, 2016); Dennis Newton, “Nephi’s Use of Inverted Parallels,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 79–106; David E. Sloan, “Nephi’s Convincing of Christ through Chiasmus: Plain and Precious Persuading from a Prophet of God,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, 6, no. 2 (1997) 67–98; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did King Benjamin Use Poetic Parallels So Extensively? (Mosiah 5:11),” KnoWhy 83 (April 21, 2016); John W. Welch, “Parallelism and Chiasmus in Benjamin’s Speech,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom”, ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 315–410; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Alma Converted? (Alma 36:21),” KnoWhy 144 (July 15, 2016); Welch, “A Masterpiece: Alma 36,” 114–131; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Chiasmus Used in Nephite Record Keeping? (Helaman 6:10),” KnoWhy 177 (August 3, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “Why and How Did Alma Explain the Meaning of the Word ‘Restoration’? (Alma 41:1),” KnoWhy 149 (July 22, 2016).

- 24. See Melvin J. Thorne, “Complexity, Consistency, Ignorance, and Probabilities,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, 179–193; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the Book of Mormon Come Forth as a Miracle? (2 Nephi 27:23),” KnoWhy 273 (February 10, 2017).

- 25. Welch, “What Does Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Prove?” 218.

- 26. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 80.

- 27. See Neal A. Maxwell, “‘By the Gift and Power of God’,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 9.

- 28. For a treatment of Chiasmus in Mesoamerica, see Book of Mormon Cenrtal, “Was Chiasmus Known to Ancient American Writers? (Mosiah 3:1–3),” KnoWhy 346 (July 31, 2017). See also Allen J. Christenson, “Chiasmus in Mesoamerica,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon, 233–235; Allen J. Christenson, “Chiasmus in Mayan Texts,” Ensign, October 1988, online at lds.org; Robert F. Smith, “Assessing the Broad Impact of Jack Welch’s Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 69–71; Allen J. Christenson, “The Use of Chiasmus by the Ancient K’iche’ Maya,” in Parallel Worlds: Genre, Discourse, and Poetics in Contemporary, Colonial, and Classic Maya Literature, ed. Kerry M. Hull and Michael D. Carrasco (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2012), 311–336.